Quartzsite - a.k.a. Tyson’s Wells

The region of southern Arizona near modern day Quartzsite became attractive to ranchers in the second half of the nineteenth century, with cattle ranching becoming prominent in the Palo Verde area as well as the area around Blythe, California. Farming, wood-collecting, and mining quickly followed. By the 1920s, the Bureau of Reclamation had become involved in water control projects along the lower Colorado River. Its efforts included levee and channel construction and dredging (USDOI 1981). With the discovery of minerals in the 1850s, Arizona began to draw a significant number of settlers, including prospectors, miners, military personnel, farmers, ranchers and salespeople (Stein 1994; Edwards 2015).

Quartzsite lies on the western portion of the La Posa Plain along Tyson Wash. The Dome Rock Mountains overlook the town on the west with Granite Mountain on the southwest edge of the town and Oldman Mountain on the northwest. The Quartzsite Footprint is an area rich in precious ores that covers 200.68 mi2 and contains many placer deposits, including the four that surround the town of Quartzsite: Middle Camp, Oro Fino, Plomosa and La Cholla (Jones 1915).

The placers on the east side of the Dome Rock Mountains, usually considered to be part of the Plomosa mining district, have been successfully worked by individual prospectors since the 1860s. The deposits at La Cholla and Middle Camp have been worked on a small scale throughout this century. From the early 1930s to 1941 La Posa Development Company conducted large scale placer production at the La Cholla placers, making it the most active district in the area for that decade. They engaged in large-scale operations at the Arizona Drift Mine from 1939 to 1941. Thousands of prospectors still fan out across the desert in search of the beautiful high gold content quartz nuggets every winter. This intensive activity has resulted in over 700 mining claims in the six townships around Quartzsite.

Today, Quartzsite is a small town that covers about five miles along Interstate 10, and extends north and south of the interstate along State Route 95, which follows Tyson Wash across the La Posa Plain. A permanent settlement near Quartzsite began in 1856 when Charles Tyson discovered reliable water and built a non-military fort to protect his water supply from attacks by Mohave Indians (Trimble 2004). The first gold rush to then Yuma County began the same year. The Arizona Territory was separated from the New Mexico Territory in 1863, and a historical marker purports the date of 1864 as when Tyson likely hand dug his well (Lucas 2010).

Fort Tyson soon became a stopover on the Ehrenburg-to-Prescott stagecoach route (a.k.a., the La Paz Road), which was a main supply route to Prescott and Fort Whipple, serving both military and civilians. The La Paz Road was about 150 miles long, over rough, unsettled Indian country (Stein 1994). In addition to carrying freight, these toll roads were used by individuals and groups of travelers, and eventually commercial stage coaches.

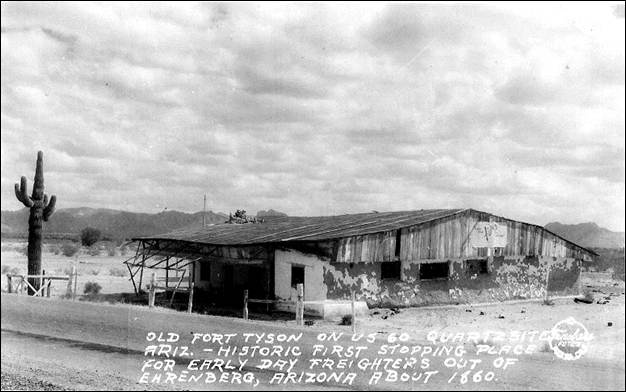

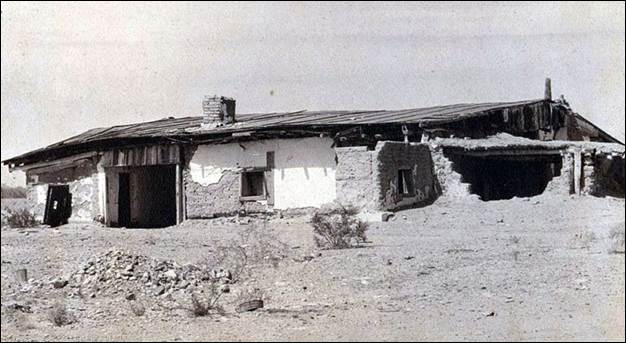

The Quartzsite Historical Society asserts that Tyson built the still extant adobe stage station in 1866 (Figures 1 and 2), the same year that the California & Arizona Stage Company began transporting passengers, mail, and Wells Fargo express from the end of the southern Pacific railroad in California to Ehrenberg and Wickenburg (Lucas 2010). The Ehrenburg-to-Prescott stagecoach route was used to transport supplies that were shipped from San Francisco and Los Angeles around the tip of the Baja Peninsula, up the Gulf of California, to the mouth of the Colorado River, and then upstream by paddle steamers to Ehrenberg (Trimble 2004). The towns of Ehrenberg, Olive City, and La Paz served miners during the 1860s gold rush around Wickenburg and in the mountains south of Prescott. The stage road forked at Wickenburg, heading north to the territorial capital at Prescott and south to Phoenix and Florence (Lucas 2010).

Figure 1. 1940s photo of Tyson's Well stage station by Frasher, facing southeast.

Figure 2. 1940s photo of Tyson's Well stage station by Glenn Edgerton, facing northwest.

Tyson's Wells offered primitive lodgings and refreshments for travelers and freight drivers (Trimble 2004; Lucas 2010). One account of the journey along the road and through Tyson's Wells comes from Martha Summerhayes, the wife of an Army officer who was stationed in Arizona. On route from Camp Verde to Ehrenberg, Mrs. Summerhayes describes the way stations as primitive but welcoming. Her entry about her stay in a tent at Desert Station in Bouse Wash, however, describes Tyson's Wells as "the most melancholy and uninviting" poorly kept ranch in Arizona. She continued to exclaim that the place reeked "of everything unclean, morally and physically" (Lucas 2010:3).

The stage stopped running when the railroad was built through the area in the 1880s, and Tyson's Wells became a ghost town. A small mining boom revitalized the town in 1897, as mining in the surrounding hills picked up in response to the introduction of more efficient gold mining methods (Trimble 2004). A post office was established as Tyson's Wells in the summer of 1893, but was closed in 1895 (Lucas 2010). In 1896, the post office reopened with the new name of Quartzsite since the postal authorities would not allow a branch to reopen with the same name. A bureaucratic misspelling resulted in an "s" being added to the mineral that was the town's namesake. It is believed that postal officials, being unfamiliar with prospecting and geology, named the town after a site where quartz is found (Lucas 2010).

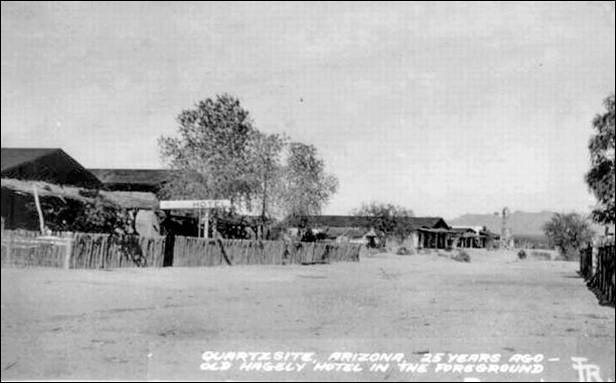

Quartzsite's population once again declined to fewer than 20 people by 1900, but the settlement was once again rejuvenated due to its location around 1910 when the Atlantic & Pacific automobile road was routed through Quartzsite. Figure 3, from 1915, shows the Hagely Hotel on the left, which was started by German immigrant Anton Hagely (1844-1928) who worked as a butcher in town during the 1890s mining boom and stayed on to become owner of a store and hotel (Lucas 2010). His wife Victoria continued the business after his death in 1928 and their son John George (1894-1977) eventually became a Quartzsite Justice of the Peace. Further down the street on the same side, is Charles V. Kuehn’s (1886-1930) general store with the windmill and water tank out front. Kuehn was a former stage driver who came to own a store and saloon and served as postmaster from 1914 to 1923 (Lucas 2010).

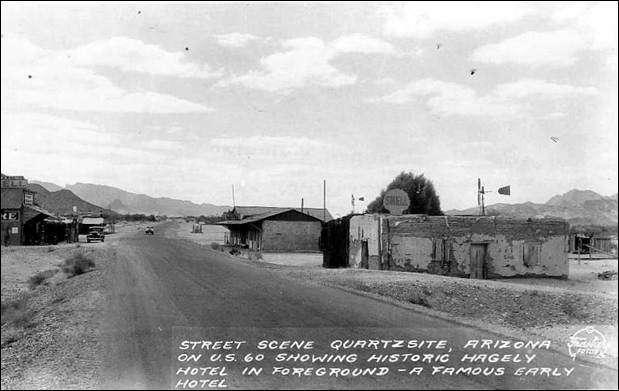

The population of Quartzsite was a few hundred in the 1930s. Figure 4 shows a view of Quartzsite in 1933, looking west along the Atlantic & Pacific Highway, which had been numbered State Route 74, and then Highways 60/70, with part of nearby Granite Mountain visible to the left behind the store. The Hagely Hotel is the building in center of the photo west of the building with the Shell sign. When this photo was taken in 1933, automobile travelers were making fewer stops in Quartzsite. Fuel and refreshments were the only appealing things to westward-bound motorists before they continued on to Ehrenberg where a through-truss bridge had replaced the ferry in 1928. In the 1930s the highway became part of US 60 and US 70.

Figure 3. 1915 photo of the Atlantic & Pacific Highway (SR74) through Quartzsite, facing east.

Figure 4. 1933 photo of Quartzsite by Fraser, facing west.

Quartzsite saw yet another decline to just 50 people by 1960 (Lucas 2010). In 1965, however, residents formed the Quartzsite Improvement Association, which sponsored the first Pow Wow Quartzsite Gem & Mineral Show (a.k.a., the Quartzsite Pow Wow) in 1967, drawing 74 exhibitors and vendors and about 1000 visitors. This initiated the winter invasion of rockhounds each year who come to the gem and mineral show and an enormous flea market (Desert USA 2015). The town was eventually incorporated in 1989, and now welcomes an estimated 1.5 million visitors a year and 250,000 temporary residents each winter. Today, Quartzsite is touted as the "dry camping capital of the world" and a "rock hound paradise" (Lucas 2010:8). It includes a public library, bank, medical centers, golf course, historical museum, and more than 70 RV and mobile home parks. Quartzsite’s coolest tourist attraction is the Hi Jolly Monument (for more information see Hi Jolly- Beale’s Camel Driver).

References

Desert USA

2015 The Desert Grasslands. Available at: http://www.desertusa.com/cities/az/quartzsite.html. Accessed September 6, 2015.

Edwards, Joshua S.

2015 Cultural Resources Survey of 67 Acres near Quartzsite, La Paz County, Arizona. Cornerstone Environmental Report No. 15-114. Flagstaff.

Jones, Edward L.

1915 Gold Deposits near Quartzsite, Arizona. Contributions to Economic Geology, 1915, Part I. USGS Bulletin 620.

Lucas, Robert

2010 Quartzsite Was in the Center of Everywhere. Available at: http://arizona100.blogspot.com/2010/11/quartzsite-was-in-center-of-everywhere.html, accessed September 24, 2015.

Stein, Pat H.

1994 Historic Trails in Arizona from Coronado to 1940: Historic Context Study. Report No. 94-72. SWCA, Inc., Environmental Consultants, Flagstaff.

Trimble, Marshall

2004 Roadside History of Arizona. Mountain Press Publishing Company. Missoula, Montana.

U.S. Department of the Interior (USDOI)

1981 Water and Power Resources Service: Project Data. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Download Quartzsite_History_121515.pdf- Tagged In: History, Mining, Quartzite

Joshua S. Edwards

Josh is the Principal Investigator for Cornerstone Environmental in Flagstaff, Arizona. He is an archaeologist, geomorphologist, and faunal analyst specializing in research topics oriented toward Southwest prehistory. This has included research on changes in prehistoric settlement patterns and subsistence strategies, anthropogenically induced paleoenvironmental change, and fluvial system dynamics and their effect on cultural landscapes. His work has been geographically focussed in Arizona and western New Mexico, and includes projects in California, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Texas. Also having a passion for history, Josh loves reading about local historical events and people. This has led him to learn the intricacies of historic preservation. Applying these principals has been an ongoing challenge and has fulfilled his desire to continue learning and expanding his abilities within his academic and professional field.