The Verde River Sheep Bridge

The Verde River Sheep Bridge (Figure 1), also known as the Red Point Sheep Bridge, is located along Bloody Basin Road, approximately 100 km north of Phoenix, Arizona, in Yavapai County. This suspension bridge was constructed to allow sheep to be driven between grazing ranges on either side of Arizona’s Verde River. Historical activities in the Bloody Basin were characterized by itinerant sheep herding, primarily staffed by Basque shepherds and laborers. A replica bridge was constructed by the U.S. Forest Service in 1989 to provide safe pedestrian access across the river to the Mazatzal Wilderness in Tonto National Forest. This article presents a brief overview of sheep ranching in Arizona, a discussion of the Verde River Sheep Bridge within this context, and several short bios of important historical individuals who were directly connected with construction and use of the bridge.

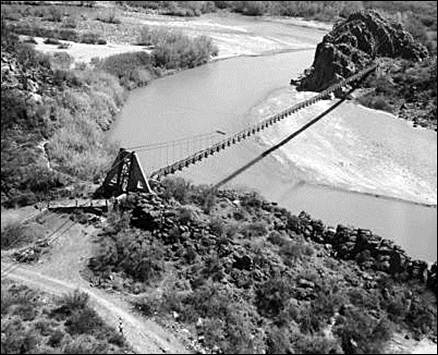

Figure 1. 1987 photo the Verde River Sheep Bridge (photo credit: Doyle 1987).

Sheep Ranching in Arizona

Sheep ranching in Arizona has roots back to Coronado's introduction of flocks to the region in 1540, when his army maintained them as meat on the hoof to feed his soldiers. It is not certain whether these animals survived in Arizona, but Navajos drove raided flocks of sheep into northeastern Arizona from the Rio Grande Valley that were introduced to New Mexico by Don Juan de Oñate in 1598 (Doyle 1987). The number of sheep in Arizona peaked in 1917 at 1,420,000, and there were only 283,000 sheep in Arizona in 1987 when the Verde River Sheep Bridge was demolished.

Once a robust, hustling stage stop, used by weary travelers, cattlemen, miners, sheep and goat herders (including the Auza and Manterola families), Cordes Station (now Cordes Junction/Cordes Lakes) was a focus of population growth in the Bloody Basin, largely due to its importance as a transportation hub for the area. The turn of the 20th century saw an influx of immigrants to Arizona, specifically to tend to the over one million sheep in the state. One such group was the Basques, including the Auza and Manterola families, who came from the Spanish and French Pyrenees Mountains where they were traditionally sheepherders (Arizona Experience 2015).

Northern Arizona sheep herders have historically migrated biannually from the mountains of the Colorado Plateau, their summer grazing grounds, to the Phoenix Basin and central Arizona, where they could pass the winter grazing their sheep on alfalfa. Due to the presence of irrigated alfalfa in the Phoenix Basin, Arizona sheepmen were able to breed and lamb their ewes earlier than ranchers in surrounding regions, giving them a distinct advantage. With the first spring lambs available in the country, Phoenix sheep herders could meet the huge demand for Easter lamb and received top dollar for their efforts.

Sharlot Hall (1908:199-200) described this annual migration as bands of sheep overflowing:

"...the mountain ranges into the deserts of the south. And then came the special fitness of Arizona for a sheep country. A sheep can go a week or more without water if he has green feed. Watering places were too few in the desert for cattle, but in winter the 'filaree' stood rank and tall, and grass started in mid-winter. The sheep wandered for miles through the cactus-covered foothills and broad valleys, came into spring rolling fat, moved slowly north for shearing and lambing, and by mid-summer were up on the mountain grass among the pines, to stay till snowfall."

Early sheep migrations did not travel formal routes, and the flocks were driven through whichever known route had easy passage and sufficient grass. There were no specific timescales for travel, and the trails linking summer and winter pastures were crossed only in the time it took the sheep to eat all the available grass along the way (Doyle 1987). Cows and horses eat foliage down to the ground so it will come back quickly, but sheep take the foliage down to the roots, which means nothing will grow back for several years (Benore 2013). This caused problems once cattle became common in northern Arizona, following the arrival of the railroad, as the sheep encroached on land coveted by powerful cattlemen.

Although sheep "driveways" in the area date back to the 1600s, they only became federally designated livestock driveways during the period from 1896 to 1918. It was not until 1919 that sheep herders could move their flocks between their summer and winter pastures without causing conflict by encroaching on cattle land (Doyle 1987). The effort for this official designation was led by the Arizona Wool Growers Association beginning in 1905, and by 1918 an extensive network of sheep driveways in central Arizona linked summer ranges in the mountains with winter pastures in the valleys. These routes varied in width from less than one mile to around two and a half miles, were marked at intervals by signs and rock cairns, and were used for many decades to follow.

Bloody Basin ewes were bred in September on the summer allotments in the mountains, several months later than ewes wintered in the Phoenix Basin (Doyle 1987). Rams were trucked from winter ranges after the ewes had arrived at the summer pastures to facilitate appropriate lambing times that would coincide with peak growth of spring grasses along the Verde and Agua Fria Rivers. Bloody Basin lambs were sold in Flagstaff, so that they could fatten on the rich grasses of the high country before market.

The spring drive from the Bloody Basin to Flagstaff saw Basque shepherds cross the Verde River Sheep Bridge with their flocks to the Tangle Creek Driveway and head northwest to Cordes. From there they would take the Beaverhead Driveway through Mayer, northeast through the Cherry Creek area, to the Verde River at the mouth of Oak Creek, all the way to Flagstaff by way of Rattlesnake Creek and Woods Canyon. The drive would begin at the bridge around April 15th by dividing the flock into bands of 1,600 to 2,000 sheep, likely crossed through the area where the Horseshoe Ranch headquarters stand today, and took around 45 days to reach Flagstaff (Doyle 1987). The latter part of this route beyond Rattlesnake Creek parallels modern Interstate 17. Fall drives back to the Bloody Basin started on October 1st, with flocks reaching the Chalk Mountain Allotment around November 15th.

The Verde River Sheep Bridge

The Verde River Sheep Bridge (aka. Red Point Sheep Bridge) was built in the summer of 1943 and was critical to the movement of sheep across the Verde River, and to sheep ranching in the Bloody Basin, for several decades. It was the last remaining suspension-type sheep bridge in Arizona and was located at the point on the Verde River approximately 500 feet downstream from the confluence of Sycamore and Horse Creeks (Doyle 1987). Approximately 500 feet downstream of the bridge is a normal-flow ford that was used prior to construction of the Verde River Sheep Bridge. The bridge was largely sponsored by Flagstaff physician and owner of the Flagstaff Sheep Company, R.O. Raymond, to facilitate movement of his flocks across the Verde River. The bridge was engineered by Cyril O. Gilliam and was built under the supervision of Frank Auza (Figure 2) and George W. Smith. Much information about the bridge comes from an interview with Mr. Auza at the bridge in 1987 prior to its demolition the same year (Doyle 1987).

Construction of the Verde River Sheep Bridge was completed with hand tools and a few mules during World War II, and it was composed largely of salvaged materials. The overall length of the structure from cable anchorage to cable anchorage was 691 feet, and the distance between the towers was 568 feet. Soon after the bridge was completed, the original wooden towers were reinforced with concrete buttresses, which are all that remains today. The walkway was 476 feet long and three feet wide and remained wood construction throughout the life of the bridge (see Figure 1; Doyle 1987). Each main suspension cable consisted of a pair of lock-coil spiral strands, which were salvaged from an abandoned tramway that carted copper ore.

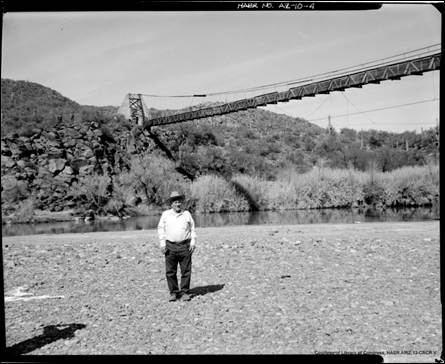

Figure 2. 1987 photo of Frank Auza, Sr. below the Verde River Sheep Bridge (photo credit: Doyle 1987).

By the mid-1920s, overgrazing by cattle caused a shift in the terms of some allotments on the Tonto National Forest from year-long cattle usage to winter sheep preference. The Chalk Mountain, Red Hill, and Pete's Cabin Allotments were located near the future site of the Verde River Sheep Bridge and were critical reasons for development of sheep herding in the Bloody Basin and construction of the Verde River Sheep Bridge.

Although the Verde River Sheep Bridge was several miles from a main sheep driveway, and was not a major migration route, it linked the Tangle Creek Driveway with the Chalk Mountain pasture and other nearby grazing allotments. It also connected the Chalk Mountain pasture on the east side of the Verde River with the Chalk Mountain ranch headquarters on the west side of the river (Doyle 1987). The Verde River Sheep Bridge was, therefore, considered to be part of an allotment and was "owned" by the Chalk Mountain Allotment permittee who sold bridge rights to nearby allotment holders. The sheep driveways had numerous unbridged stream crossings in the high elevations where watercourses were shallow and could be forded by flocks with little risk of losing sheep.

At least two other permanent suspension-type bridges (at Bartlett Dam and Horseshoe Dam) and two temporary bridges (a pontoon type at the mouth of Red Creek and a small suspension type bridge just downstream from the Verde River Sheep Bridge) existed along the Verde River. Both of the temporary bridges were erected each fall and dismantled in the spring prior to seasonal flooding. Once the Verde River Sheep Bridge was constructed in 1943 the temporary bridges were no longer used (Doyle 1987).

Bloody Basin saw much sheep activity before 1905 and after 1926, but sheep that wintered in the Bloody Basin never saw any irrigated alfalfa. Instead, they foraged on grass and Spanish-introduced alfilaria (aka. filaree), which sprouted after winter rains. During the spring, sheep herding activity in the Bloody Basin picked up dramatically when the grasses were lush and lambs could feed at the height of grass growth in April.

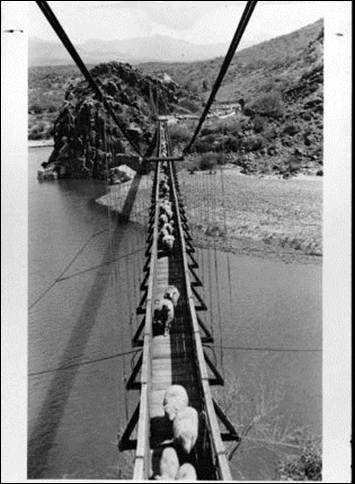

In addition to the annual movement of flocks of sheep across the river, the Verde River Sheep Bridge was used daily by sheepherders that were moving between pastures and headquarters on opposite sides of the river, and by burros carrying provisions. The Verde River Sheep Bridge was a vast improvement over previous methods of crossing the Verde River, and there could be as many as 142 sheep on the bridge in a single file line, with up to twice that amount if necessary (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Historic photo of sheep crossing the Verde River Sheep Bridge (photo credit: Frank Auza, Sr.)

The Verde River Sheep Bridge became the hub around which traditional winter activities took place for all sheep outfits in the Bloody Basin (Doyle 1987). As many as twelve thousand sheep crossed the bridge at least four times per year. This occurred in the fall when moving from summer pastures in the Flagstaff area to the winter pastures in the Bloody Basin, before and after shearing in February, and in the spring when returning to the summer ranges in the high country. Frank Auza would hire extra employees at this time to help with herding, shearing, lambing, tending camp, and controlling local predators.

Basque sheep herders would walk the bridge checking for loose boards, the first animals to cross would have to be pushed to begin the bridge crossing, and one Basque sheepherder would count the sheep as they reached the west bank. Shearing took place on the west side of the river (for three nearby allotments) so the wool could be trucked to market along what is now Bloody Basin Road, as there were no roads on the east side of the river at that time. The Verde River Sheep Bridge, along with a barn, open shearing shed, and corrals on the west side of the river, were maintained by seasonal Basques hired by Auza. In 1943, 11,000 sheep were sheared at the location producing 100,000 pounds of wool (Doyle 1987).

The Verde River Sheep Bridge is important in Arizona state history for its relation to the sheep-raising industry, and due to its construction largely by immigrant Basque sheepherders with little technical assistance. The shortage of young Basque sheep herders, along with importation of lamb and mutton from New Zealand and Australia and the development of synthetic fibers that replaced wool, is credited with the abandonment of the Chalk Mountain Allotment and the Verde River Sheep Bridge by the Manterola family in 1984. The bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, demolished in 1987, and replaced with a foot bridge in 1989 (Figure 4). The original west suspension tower still remains alongside the replica bridge.

Figure 4. 2012 photo of the New Verde River Sheep Bridge.

Important Individuals in the History of Bloody Basin

Several individuals and their families were instrumental in the development of sheep ranching in the Bloody Basin and the construction and maintenance of the Verde River Sheep Bridge, including Dr. R.O. Raymond, Frank Auza, Jose Manterola, and John W. Hennessy. Dr. R.O. Raymond acquired the Chalk Mountain Allotment (on the east side of the Verde River) in 1942 and quickly decided to build a bridge across the river that would accommodate his 4,852 sheep. Frank Auza was Raymond's foreman and was instrumental in the bridge's construction (Doyle 1987).

High water levels in the spring had previously proved difficult for herders who were forced to swim the sheep across the river, inevitably resulting in the loss of livestock. Raymond's War Production Board Application letter from 1943 (since construction materials were scarce and difficult to obtain during World War II) states that "Construction of this bridge will reduce losses for 6 sheep outfits in crossing Verde River during lambing time and will increase utilization of feed by allowing sheep to graze greater area than is now possible" (Doyle 1987:15).

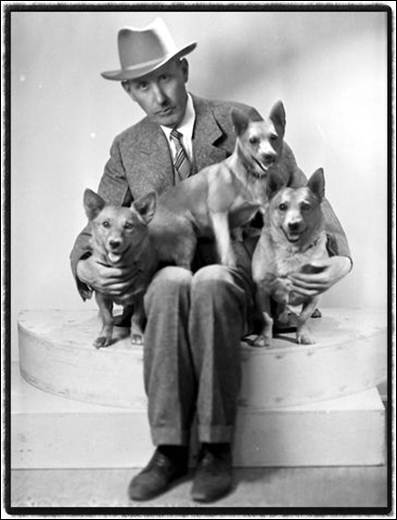

R.O. Raymond was a physician and also the principal patron of the Verde River Sheep Bridge, paying for the majority of its construction costs (Figure 5). Raymond was born on September 5, 1876, graduated from medical school in St. Louis in 1899, and moved to Arizona for his health in 1904. He practiced medicine in Flagstaff and entered the sheep business prior to World War I. Raymond owned the Flagstaff Sheep Company and was a partner of Ramon Aso in the Howard Sheep Company until 1944. After acquiring the Chalk Mountain Allotment in 1942 Raymond applied to the Tonto National Forest for a permit to build the Verde River Sheep Bridge on his allotment the same year. Once significantly established, Raymond became quite a philanthropist, donating land for the Flagstaff Community Hospital, the Raymond Antelope and Buffalo Refuge (although this may have been a land sale), and the Flagstaff Armory. Additionally, he gave Lindberg Springs to the State of Arizona and founded the Flagstaff (now Raymond) Educational Foundation. R.O. Raymond died on July 5, 1959 (Doyle 1987).

Figure 5. Historic photo of Dr. R.O. Raymond and his dogs (photo credit: Raymond Educational Foundation website).

Frank Auza, Sr., a Spanish Basque, is one of the most interesting and influential people that helped shape the history of the Bloody Basin (see Figure 2). He was born March 3, 1905 in Lizaso, Navarra, Spain to Jacinto and Antonia Auza, both of whom were natives of the Basque Country (Arizona Daily Sun, September 30, 1999). Along with his mother, brother and sisters, Mr. Auza immigrated to the United States in 1915 when he was ten years old to join his father and brother on a sheep ranch in Phoenix. He began herding sheep at the age of 10 with his brothers, and would be involved in sheep ranching for the remainder of his life (Doyle 1987). After his father's death in 1920, the Auza family moved to Flagstaff where his mother died of pneumonia two years later.

Mr. Auza began as a sheepherder and later became a foreman of Dr. Raymond's Flagstaff Sheep Company and the Howard Sheep Company where he worked from 1933 to 1945 (Doyle 1987). He oversaw the companies' Bloody Basin sheep operations during the winter months and was foreman for the movement of the sheep to the Flagstaff area pastures during the summer months. When he was not busy with the sheep he labored on the construction of the bridge and organized and paid the Bloody Basin Road and bridge laborers, and he maintained the bridge until his retirement in 1979 (Figure 6). Auza was also foreman for the Manterola Sheep Company from 1945 to 1961. He purchased the Lockett Sheep Company and formed the Auza Sheep Company in 1959 and had feeder lambs in Tacna, in southwestern Arizona. He was a member of the Arizona Wool Growers Association, The Western Range, and a lifetime member of the Sheriff's Posse in Flagstaff. He was also the official cook for the annual Wool Growers barbecue picnic from 1926 until his sons took over the job.

Figure 6. 1987 photo of Frank Auza, Sr.'s inscription in the concrete of the Verde River Sheep Bridge (photo credit: Doyle 1987).

He married Elsie Barreras of Flagstaff (born in Magdalena, New Mexico) on October 15, 1933, and had eight children with her, seven of whom are/were in the sheep business or are married to sheep ranchers. Frank and Elsie were married for 65 years. After retiring in 1979 he spent his winters in his Tacna home and summers in his home in Flagstaff. Mr. Auza died at his home at the age of 94. The Auza and Manterola families are still actively living and maintaining the state’s sheep culture (Arizona Experience 2015).

Frank Auza, Sr., was survived by his wife, Elsie; his brother Joe Auza, of Rodeo, California; his sister Martina Auza Imerone, of Crockett, California; and his children, Frances Jorajuria, of Tacna; Joe Auza, of Casa Grande; Frank Auza Jr., of Roll.; Pete Auza, of Yuma; Johnny Auza, of Roll; Martin Auza, of Yuma; George Auza, of Tacna; and Elsie Jorajuria, of Tacna. At the time of his death in 1999 he had 21 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren (Arizona Daily Sun, September 30, 1999). His funeral Mass was held at The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Chapel in Flagstaff and he is buried at Calvary Cemetery.

Jose Antonio (Tony) Manterola, also a Spanish Basque, arrived in the United States in 1907 from Spain and bought the Flagstaff Sheep Company from Dr. Raymond in 1945. He wintered his sheep on the Chalk Mountain Allotment in Bloody Basin, and in Casa Grande. Manterola maintained the shearing corrals, barn, horse corrals, a three-room cabin, a caretaker's cabin, a wood shed, and a chicken coop on the west side of the Verde River near the bridge, and used the Verde River Sheep Bridge to cross the river with sheep, supplies, and men, to the east side of the river, where the winter pastures were located. Manterola died November 23, 1956, but the family kept the Chalk Mountain Allotment and continued to maintain the bridge and use it for sheep until 1979. Only burros were wintered on the Chalk Mountain Allotment after 1979, and the Manterola family relinquished the allotment in 1984 (Doyle 1987).

Portions of nearby Horseshoe Ranch, west of the bridge along Bloody Basin Road, were purchased by an association of sheep ranchers in the 1940s, including Tony Manterola. They sold Horseshoe Ranch to sheep and cattle rancher John W. Hennessy in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Although little is known about Hennessey’s tenure at Horseshoe Ranch, it is thought that he was the first rancher to establish a fixed ranching operation on the property. It is believed that Hennessy is responsible for building a small adobe residence at the ranch headquarters, and for constructing the original alignment of Bloody Basin Road to provide access to his newly constructed headquarters (Grandrud n.d.; Edwards et al. 2015). Hennessy held the Red Hill Allotment in 1949, which he used for sheep grazing. He listed the Verde River Sheep Bridge as a range improvement on grazing permits issued to him by the Tonto National Forest in 1949 and 1952. Hennessy was born in Flagstaff in 1902, sold Horseshoe Ranch in 1956, and died February 21, 1958.

The Auza and Manterola families historically trailed their sheep from the winter range in Casa Grande to the summer pastures in the north. Today, they truck the sheep from Casa Grande to Cordes Junction, and then trail the sheep north. Trailing the sheep is good for the health of the sheep and improves lambing in November. The Black Canyon and Beaverhead-Grief Hill Sheep Driveways have been used for over a century and are still used by the Auza and Manterola families every year to bring sheep from their winter pastures in the south to summer pastures on the Mogollon Rim.

References

Arizona Experience

2015 Sheep Herding in Arizona. Electronic document, http://arizonaexperience.org/people/sheep-herding-arizona, accessed July 16, 2015.

Benore, Loretta

2013 In Days of Yore: The True Story of How Bloody Basin Got Its Name. Verde Independent, July 24, 2015.

Doyle, Gerald A.

1987 Verde River Sheep Bridge (Red Point Sheep Bridge). Historic American Engineering Record No. AZ-10 (HAER ARIZ, 13-CACR.V, 1) by Gerald A. Doyle and Associates.

Edwards, Joshua S., Kimberly Spurr, Michael O’Hara, and David E. Purcell

2015 Cultural Resources Report on Monitoring of Water Main and Spring Line Installation at Horseshoe Ranch, Yavapai County, Arizona. Cornerstone Environmental Consulting Report No. 15-105, Flagstaff.

Grandrud, R.

n.d. The Horseshoe Ranch. Unpublished manuscript on file at the Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix.

Hall, Sharlot Mabridth

1908 Old Range Days and New in Arizona. Out West Magazine Co., Los Angeles.

Leighty, Robert S.

1998 Tertiary Volcanism, Sedimentation, and Extensional Tectonism across the Basin and Range–Colorado Plateau Boundary in Central Arizona. In Geologic Excursions in Northern and Central Arizona: Field Trip Guidebook for Geological Society of America Rocky Mountain Section Meeting, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, edited by E. M. Duebendorfer, pp. 59–95. Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff.

2007 Geologic Map of the Black Canyon City and Squaw Creek Mesa Area, Central Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Map CM-07-A. Arizona Geological Society, Tucson.

Download Verde_River_Sheep_Bridge_121515.pdf- Tagged In: Arizona, Basque, History

Joshua S. Edwards

Josh is the Principal Investigator for Cornerstone Environmental in Flagstaff, Arizona. He is an archaeologist, geomorphologist, and faunal analyst specializing in research topics oriented toward Southwest prehistory. This has included research on changes in prehistoric settlement patterns and subsistence strategies, anthropogenically induced paleoenvironmental change, and fluvial system dynamics and their effect on cultural landscapes. His work has been geographically focussed in Arizona and western New Mexico, and includes projects in California, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Texas. Also having a passion for history, Josh loves reading about local historical events and people. This has led him to learn the intricacies of historic preservation. Applying these principals has been an ongoing challenge and has fulfilled his desire to continue learning and expanding his abilities within his academic and professional field.